Entering the cybersecurity field does not follow a single, linear path. The current ecosystem is vast and constantly evolving, requiring a flexible, modular, and continuously updated roadmap. It’s not enough to learn techniques or tools: it’s essential to understand the different professional roles, the logic behind each domain, and how they interconnect. This demands a solid foundation on multiple levels, technical, methodological, regulatory, and strategic.

Everything starts with the fundamentals of operating systems, networking, and programming. It doesn’t matter whether someone aims to specialize in forensics, pentesting, or active defense: without understanding how TCP/IP works, how networks are segmented, how an application runs in memory, or how privilege escalation happens, any specialization will be lacking. It’s critical to master Linux at the command-line level, Windows at the administrative level, and networking at the OSI layers, including hands-on practice with sniffing, VLANs, NAT, firewall rules, and VPN tunnels. In programming, Python remains the sector’s universal language, followed by bash/powershell scripting and basic knowledge of C/C++ for low-level exploit understanding.

The next layer is generalist security. This includes topics such as threat modeling, risk analysis, technical and organizational controls, applied cryptography, strong authentication, vulnerability management, and the use of essential tools like Nmap, Nessus, Wireshark, or Burp Suite. It’s also the time to study standards like ISO/IEC 27001, NIST 800-53, or the MITRE ATT&CK framework. Additionally, one should learn what logs are, how they are collected, how to detect anomalies, and how to triage incidents.

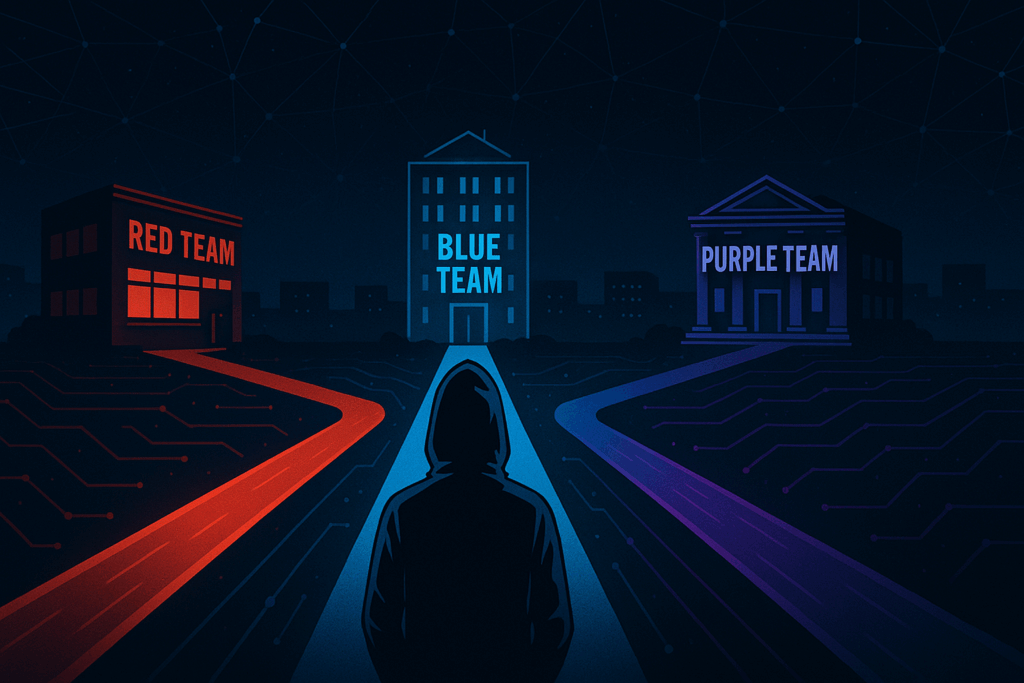

Once this core is in place, several distinct paths emerge, each with its own rationale. One of the most well-known is the Red Team path, focused on offensive operations. Training here involves pentesting, ethical hacking, exploit development, lateral movement, and EDR evasion. Tools like Metasploit, Cobalt Strike, BloodHound are commonly used, along with skills in social engineering, phishing, persistence techniques, and attacks against Active Directory. Relevant certifications include OSCP, CRTO, and PNPT.

On the opposite end is the Blue Team, focused on defense. The emphasis here is on detection, containment, and response. It involves working with SIEM platforms (such as Wazuh, Splunk, or Sentinel), EDRs, honeypots, YARA rules, malware analysis, and incident response. You’ll need to learn how to investigate suspicious hashes, reconstruct attack chains, contain compromised endpoints, or respond to ransomware. Certifications such as GCIA, GCIH, or Blue Team Level 1 are relevant in this track.

Between them lies the Purple Team, not so much a job title as a mindset of collaboration. Professionals in this space must understand both offensive and defensive techniques, but most importantly, know how to communicate findings, correlate results, and close the improvement loop. It’s not about running tools but about translating Red Team findings into defensive rules for the Blue Team—and vice versa.

Another entirely different route is Governance, Risk, and Compliance (GRC). This path is mostly non-technical but requires a deep understanding of technological risks. It involves mastering frameworks (like ISO 27001, TISAX, ENS, PCI-DSS, or GDPR), coordinating audits, defining policies, managing assets, and leading continuous improvement projects. Professionals in this area often come from management or consultancy backgrounds and pursue certifications such as CISM, CISA, or ISO Lead Implementer.

There are also more vertical specializations: malware analyst, who dissects binaries and reverse engineers code with IDA or Ghidra; cloud security specialist, who audits AWS/Azure/GCP architectures using CIS Benchmarks; security architect, who defines infrastructure controls; DevSecOps specialist, who integrates security into CI/CD pipelines; cryptographer, who designs protocols; and awareness trainer, who translates complex concepts into accessible language. Each requires specific knowledge and constant learning.

The roadmap must adapt to each person’s background. Someone with experience in systems or networking may progress faster in Blue Team or DevSecOps. A developer might pivot toward AppSec or security automation. A non-technical profile with strong organizational skills can bring value in the GRC space. The key is accepting that cybersecurity is a field of perpetual learning. Curiosity, trial-and-error skills, and constant reading of papers, forums, and CVEs matter more than any formal course.

Formal education (degrees, master’s programs, bootcamps) can accelerate progress, but it’s no substitute for practice. Setting up local labs with vulnerable machines (from TryHackMe, HackTheBox, or VulnHub), contributing to open-source projects, participating in CTFs, or doing real-world analysis in simulated environments make a real difference. All of it must be paired with critical thinking: understanding why a technique works, what vulnerability it exploits, and how to mitigate it.

In short, cybersecurity is not a destination but a dynamic playing field where every professional must build their own path based on a strong foundation, a specific focus, and a mindset of continuous improvement. The diversity of roles is not an obstacle but one of the field’s greatest strengths. And it’s this diversity that ensures there are as many valid roadmaps as there are people willing to enter this world.